UNC researcher Dr. John Bruno and Dr. Margarita Brandt of USFQ are partnering on a three year, one million dollar grant from the National Science Foundation to untangle the interactive roles of temperature, nutrient flux, and predation in structuring the Galapagos marine food web. The project is titled “Temperature Regulation of Top-Down Control in a Pacific Upwelling System” and all work will take place at the Galapagos Science Center on San Cristobal, Galapagos. According to Brandt, “This new funding will allow us to understand the effect of temperature on the structure and the functioning of the Galapagos marine ecosystems.”

Nearly all the animals that inhabit the ocean are “cold-blooded” or ectothermic, meaning their body temperatures match the temperature of the ocean around them. This has important consequences for their physiology and more broadly for the way marine ecosystems function. When ectotherms warm up, their metabolism increases; meaning they breathe more rapidly, and eat more just to stay alive. This is bad news for prey since a warm predator is a hungry predator. But warming also enables prey species to crawl or swim away more quickly when being hunted. Thus, everything speeds up in warm water. Energy flows more quickly from the sun to seaweeds (via photosynthesis), to the herbivores, then on up to the large predators at the top of the food chain.

The research team, led by Bruno and Brandt, is testing these ideas in the Galapagos Islands to determine how temperature influences marine ecosystems. Ongoing work in this iconic natural laboratory is helping marine ecologists understand the role of temperature and how this and other ecosystems could function in the future as climate change warms the ocean. Other broader impacts of the project include student training and on-site outreach to tourists and the local community about ocean warming and some of the lesser-known species that inhabit the Galapagos.

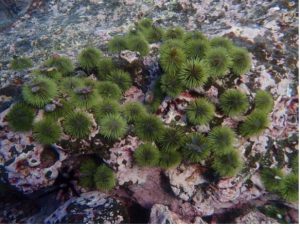

The broad goal of this project is to understand the effect that temperature has on patterns and processes in upwelling systems. “Our findings will also help us to forecast how global warming will affect this unique ecosystem in the near future,” says Bruno. Specifically, the team is measuring the temperature-dependence of herbivory and carnivory in rocky subtidal habitats of the Galapagos. They are performing field experiments to measure the relative and interactive effects of temperature, herbivory, and nutrient flux on the productivity and standing biomass of benthic macroalgae. Additionally, they are using in situ predation assays across spatial and temporal temperature gradients and mesocosm experiments to determine the relationship between ocean temperature and predation intensity for predator-prey pairings including whelk–barnacle, sea star–urchin, and fish–squid.

The team is also looking to have broader impacts in the Galapagos and beyond. The project findings will help scientists and managers anticipate how ongoing anthropogenic warming in this region will impact the ecosystem and the invaluable resources and services it provides. The project outreach also includes training Latino (mainly Ecuadorian) high school, undergraduate, and graduate students. All will receive research experience on-site under the guidance of the PI. This training will increase science capacity in the region and employment opportunities to the many young Galapagueños interested in science and natural history by providing them with skills and experience.

To learn more you can view this comprehensive video about the broader project and also a recent talk about this project by UNC Graduate Student Isabel Silva.